(Host) For those old enough to have watched on television, the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon are so vivid and personal, it’s hard to imagine they could ever be forgotten.

But today’s high school sophomores were in kindergarten when those attacks took place. And for many younger students, "9/11" is no more personal than Pearl Harbor or the Korean War.

As part of our series on how 9/11 has affected us, VPR’s Susan Keese reports on the evolving challenge of teaching about the 2001 terrorist attacks.

(Keese) Sandra Cortes was teaching kindergarten when the terrorists struck. She reflected on it recently at the farmer’s market in Brattleboro.

Cortes didn’t own a television.

(Cortes) "So I hadn’t seen any of the horrifying images of that day. But the next day, September 12, the children went to the block area immediately. And they just built towers and knocked them down… they built them and they knocked them down."

(Keese) To Cortes the toppling towers meant a loss of innocence and a world forever changed.

(Keese) Ten years later, some of the kindergartners Cortes watched that day could be here – at a girl’s hockey practice at Brattleboro Union High School.

Ashley Maguire is a Freshman now.

(Maguire) "I didn’t really understand at the time but I remember everyone like crying… and I was really confused… It made me very frightened because I ride back and forth in planes all the time every year to see my dad in Charleston… it’s really scary…"

(Keese) Senior Sammie Jarvis, who was seven, says she thinks about it a lot.

(Jarvis) "It’s not an everyday worry for me, but, you know – nothing’s really safe in this world today. I mean, it could happen again."

(Keese) Mike DiMaio teaches Social Studies at Mount Anthony Union. He went to high school in the nineties when, he says, the world seemed safer than it does now – even to kids who were very young when the attacks occurred.

(DiMaio) "They don’t have much memory of what happened, but this is still something that has been hanging over their heads for the past ten years. I have to say I think they do feel more unsafe. The only thing is, I don’t know if they know it…"

(Keese) This past summer, DiMaio and a colleague put together a summer school course on 9/11.

(DiMaio) "And not just September 11 but the world that’s come out of it. The two wars, some of the challenges here at home with civil liberties and security. We realized in a 3 week program it gave us a lot of issues to tackle."

(Keese) They started by asking students to write down what they already knew about the 2001 attacks.

(DiMaio) "Some students didn’t know that there were four attacks… Some didn’t know about the Pentagon. Some didn’t know the difference between the two wars that we’re involved in…"

(Keese) The class developed a timeline. They looked at events before that day: the Soviet Wars in Afghanistan, Al-Qaeda’s 1993 attempt at bombing the World Trade Center, the suicide bombing of a US Navy vessel in Yemen in 2000.

(DiMaio) "I think they sort of feel like Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaeda came out of the wilderness on September 11… probably from some part of their nightmare… and tore the twin towers down. But in reality this was something that had roots that went back decades."

(Keese) DiMaio’s students studied religious fundamentalism in its different guises. They read case studies of the 9/11 hijackers and of terrorists from a variety of cultures and backgrounds – to broaden their definition of who might turn to terrorism and why.

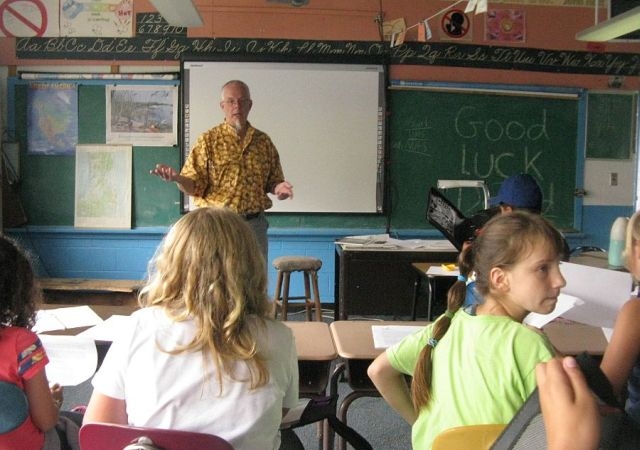

Joe Rivers teaches social studies at Brattleboro Area Middle School. He was in his classroom during the attacks of 2001. He’s been there ever since, watching as each new class of students moves further from the actual experience of that day.

Rivers’ current crop of middle schoolers have no personal memories of 9/11.

(Rivers) "For the students I have now, it’s only a piece of history. As much as the Civil War is a piece of history or Vietnam is a piece of history. The only thing that’s different is they may know people who can tell them stories about that time."

(Keese) Rivers introduces 9/11 to his students by getting them to ask their families for their memories of that day. It’s often something they haven’t talked about.

(Rivers) "Oftentimes parents don’t want to discuss it with the kids when they’re young – the threats and the violence and the terror and the worry. But by the time they get to middle school it’s time to start exploring those things."

(Keese) The students come back with diverse and often conflicting stories from the adults in their lives. Rivers says that’s when the questions get interesting.

(Rivers) "Almost never do the students come back able to say why the attacks happened. The why question is I think the one we’re all struggling with, but it’s one that students want to know."

(Keese) Rivers says the Brattleboro Middle School expects that students will come from local grade schools with very little structured knowledge of the attacks.

But at Marlboro Elementary school, students in David Holzapfel’s fifth and sixth grade class plan a trip to New York City every other year.

Holzapfel says topics relating to Ground Zero are a popular choice for the research project each student does relating to the trip. He says one student last year tried to piece together the events leading to the attacks.

(Holzapfel) "What was an eye-opener for me was the fact that this young lady, who was studying the background, started talking to the other students and was astonished at how few knew anything about it. Didn’t even know what it was."

(Keese) Holzapfel says the student, who graduated last year, speculated that most adults find the topic too painful to discuss it with their children.

Zev-Kazati Morgan, a sixth grader this year, thinks they worry needlessly about upsetting the kids..

(Kazati-Morgan) "I mean I could see how it could be very upsetting. But I’m not upset by it."

(Keese) Morgan Brook deBock, another sixth grader, studied the designs for the new buildings going up on Ground Zero.

(Brook deBock) "I learned about some of the safety systems they were going to put in the new towers to make sure everyone was evacuated easily if there was a problem ."

(Keese) Brook deBock says it wasn’t because he was worried, but because he wanted to do a project that would yield some concrete information.

He’s heard so many things about Ground Zero that didn’t seem to fit together.

Mike DiMaio of Mount Anthony Union says that’s one of the challenges of trying to teach about history that’s still unfolding.

(DiMaio) "You know, I don’t think anyone’s ever going to forget about these events, but their place in history has yet to be solidified."

(Keese) The way September 11 is taught and remembered will also continue to evolve. The outrage and emotion of a decade ago may fade. But DiMaio says the lessons of 9/11 and its aftermath are just beginning.

For VPR News, I’m Susan Keese.

Visit VPR’s Remembering 9/11 Page