(Wood flute music up full, then fade behind and out)

(Mitch Wertlieb) World War II played out on many fronts, including the one at home. There was, of course, no warfare here. But there was a battle of sorts over identity. And for people who looked like the enemy, there were consequences.

(Wade) It’s easier to identify a person who looks clearly different from you and from me than it is to identify a person who thinks differently.

(Wertlieb) Ken Wade is an associate professor at Champlain College with a long time interest in World War II propaganda, and the practice of stereotyping the "enemy."

And that’s where we conclude our Vermont Reads series.

Good morning. I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

The Vermont Humanities Council, which sponsors an annual statewide community reading program, chose When the Emperor Was Divine this year. It’s a fictional account by Julie Otsuka of the World War II internment of people of Japanese descent.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, America mobilized for war. And Wade says that in order to prepare psychologically and to motivate people to risk their lives to fight an enemy, that enemy has to be demonized and made to look as evil as possible

(Wade) The Japanese were demonized to an extent that we hadn’t seen since WWI when we demonized the Germans – as the Hun, the ruthless Hun.

(Wertlieb) An old newsreel from that time gives a sense of the attitudes.

(newsreel excerpt)

(Wertlieb) During World War II, some very surprising people produced some extreme images. There’s a poster promoting war savings bonds that shows a Japanese man wearing glasses, with extreme buck teeth. The poster says: "Wipe the sneer off his face." It’s signed by Dr. Seuss.

(Wade) Theodor Geisel was a humorist/cartoonist working in advertising. It was only after the war that he really rose to prominence as one of the most beloved children’s authors… you know that the Disney corporation participated in this propaganda push as well.

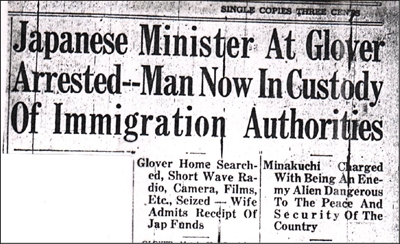

(Wertlieb) And it was effective – contributing to an atmosphere of fear and suspicion, in which American citizens could be interned without public outcry. And a respected, long time resident of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom could be arrested as a spy. Joan Alexander of Glover was researching family history when she came across the story.

(Alexander) I had a great aunt who had a brother in law who was Japanese. And he had lived in Glover and his name was Yutaka Minakuchi – is how we knew his name.

(Wertlieb) His grandparents had converted to Christianity under a missionary program and he came to the United States as a young man to study for the ministry. He stayed and became a lecturer. He met Nellie Cook from Glover. They married, settled down and started a family in Glover – where for 20 years, he was a respected member of the community. In the years before the war, he was said to be the only Japanese subject living in Vermont, and the only Japanese minister in the country. But with the war, things changed.

Alexander recalls coming across a startling headline one day as she looked through newspaper archives.

(Alexander) "Japanese minister arrested as a spy" and I was totally shocked because nobody in my family had ever mentioned this. And so I decided then I would try to figure out what was this story and in the end I put together what I had for the Glover Historical Society.

(Wertlieb) Was there any real, hard evidence that led to his arrest – that the government made known to the newspapers, to the town, to anyone?

(Alexander) The fact that he was getting a stipend from Japan and had been ever since he had left his job in Peacham as the minister where he had been for ten years – people really latched onto that as proof that he must be a spy. And there had been a lot of talk that he was sending coded messages from a radio and there was an antenna up in back of their home in Glover. And it was true that there was a radio, but they searched for the antenna and never found anything like that.

(Wertlieb) After the war Minakuchi found work in New York and Pennsylvania as a butler, with Nellie as housekeeper. When it was finally legal for him to do so, he became a naturalized citizen. After Nellie’s death, he returned to Vermont, where he died one year before President Gerald Ford apologized and rescinded Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, calling for wartime internments.

After the war, the 120,000 men, women and children who had been held by the U.S. government were released. Most had to start over from scratch. But they got on with it, despite lingering confusion over cultural identity.

After the war, the 120,000 men, women and children who had been held by the U.S. government were released. Most had to start over from scratch. But they got on with it, despite lingering confusion over cultural identity.

Where and how to return home – how to once again "belong" – is one of the final themes in this year’s Vermont Reads book, "When the Emperor was Divine." Author Julie Otsuka reads an excerpt:

(Otsuka) WE WERE FREE NOW, free to go wherever we wanted to go, whenever we pleased. There were no more armed guards, no more searchlights, no more barbed-wire fences. Our mother went out to the market and brought back the first fresh pears we had eaten in years. She brought back eggs, and rice, and many cans of beans. When our ration books arrived, she told us, she would buy us fresh meat. She dug up the silver she had buried in the garden before we had left and she set the card table for three. The knives were still sharp. The forks and spoons had not lost their shine. As we sat down in our chairs she reminded us to eat slowly, with our mouths closed and our heads held high above our plates. "Don’t shovel," she said.

But we could not help ourselves. We were hungry. We were ravenous. We ate quickly, greedily, as though we were still in the mess hall barracks, where whoever finished first got seconds and slow eaters were left behind to make do with only one serving.

Later on, in the evening, we turned on the radio and heard one of the same programs we had listened to before the war – The Green Hornet – and it was as if we had never been away at all. Nothing’s changed, we said to ourselves. The war had been an interruption, nothing more. We would pick up our lives where we had left off and go on. We would go back to school again. We would study hard, every day, to make up for lost time. We would seek out our old classmates. "Where were you?" they’d ask, or maybe they would just nod and say, "Hey." We would join their clubs, after school, if they let us. We would listen to their music. We would dress just like they did. We would change our names to sound more like theirs. And if our mother called out to us on the street by our real names we would turn away and pretend not to know her. We would never be mistaken for the enemy again!

(Wertlieb) Julie Otsuka reading from When the Emperor Was Divine, her fictional account of a pivotal time in American history.

More resources about Vermont Reads and the Vermont Humanities Council can be found on our Web site, vpr-dot-net.

For VPR News, I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

Explore the entire series: