(Mitch Wertlieb) Thousands spent World War II in "camps," held by their own government.

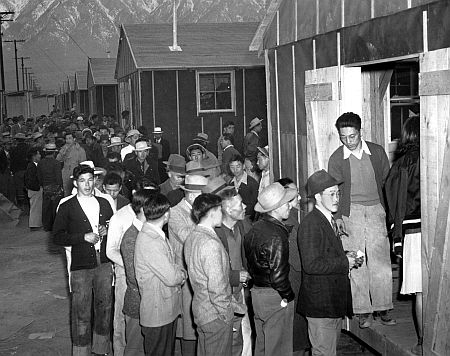

(Yamashita) "They were called relocation centers and they were called internment centers…but they were prison camps…they were behind barbed wire."

(Wertlieb) Dorothy Whitney Yamashita’s late husband, Stan, was one of them … the 120,000 ethnic Japanese interned during World War II. Like two-thirds of those sent to the camps, he was an American citizen. More than half were children including a number of orphans.

I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

This week, we’re examining the internment of people of Japanese descent through our series, Vermont Reads. This is a collaboration with the Vermont Humanities Council to support its one-book, state-wide, community reading program.

This year, the Council selected When the Emperor Was Divine, Julie Otsuka’s fictional account of a Japanese-American family’s life in the camps.

The Japanese were not the only nationalities targeted. 11,000 people of German ancestry were relocated, as were 3,000 people of Italian ancestry, along with a number of German Jewish refugees – since the U.S. Government didn’t differentiate between ethnic Jews and ethnic Germans. There were also American-born citizens and children among these smaller groups.

And most often, "relocation" meant being forcibly held in an internment camp run by the military, complete with guard towers and barbed wire fences.

A government film from that era gives a feel for everyday life in the camp.

(Wertlieb) Lafayette Noda lives today in Meriden, New Hampshire. During the war years, he spent time in a camp. He remembers the time a Quaker friend tracked him down, and came to see if he could help.

(Noda) "We had to talk through the fence. He could come to the fence near the gate, but then we had to go to that particular part of the fence because we were inside the barbed wire fence around the camp."

(Wertlieb) Images like this sometimes inspire comparisons with Guantanamo, or even with Nazi Germany. But Mark Stoler, Professor emeritus of History at the University of Vermont, says there was a big difference.

(Stoler) "The purpose of Auschwitz is to kill people, either directly exterminate them or work them to death. The purpose here is to remove these people, to isolate them and that is what is done. They are deprived of their property, they are deprived of their rights, they are put behind barbwire, it is not constitutional, it is not legal…"

(Wertlieb) … but it is war time and the practice is generally accepted as a military necessity. So was another little known hallmark of the era – German Prisoner of War camps. By the end of the war, 425,000 prisoners of war were being held in nearly every state of the union – mostly in the South to save on heating costs. But POW labor was much in demand, even in the pulpwood industry of northern New Hampshire. Allen V. Koop is the author of "Stark Decency: German Prisoners of War in a New England Village."

(Koop) "The largest paper company in NH, the Brown Paper Co. in Berlin, NH, could not meet its war time contract for cardboard and pape,r the company asked the War Dept. to send some prisoners of war to help cut some pulpwood so they could make their war time contract."

(Wertlieb) Roughly 300 German POWs and 50 or so US Army guards were assigned to a former CCC camp on the main road that runs through the village of Stark, population 400. The Germans had been opponents of the Nazi government. They were Communists or Social Democrats, who had served time in German prisons for anti-Nazi activities before being pressed into military service.

(Koop) "So, Camp Stark from the very beginning had a large anti Nazi population to which was then added about 100 very young 17 to18-year-old German boys who were captured their first day in combat in France and they were not very Nazi in their opinions."

(Wertlieb) And there in the isolated depths of the northern forest, challenged by harsh weather and heavy work quotas, friendships formed. Years later, prisoners and guards would even hold a reunion. It’s a remarkable story of the human spirit overcoming adversity.

According to Lafayette Noda, people tried to make the best of harsh conditions in the internment camps, too.

(Noda) "I helped with schooling, and it happened because of my background in chemistry. Others worked in the kitchen, others in general clean-up… People volunteered, different things."

(Wertlieb) Indeed, many internees managed to pass the time at camp creatively. Dorothy Yamashita still has several small, bird-shaped wooden pins her father-in-law carved by hand. And Tracey Tsugawa’s family treasures four pieces of sculptural wood fashioned by her grandfather.

(Wertlieb) Indeed, many internees managed to pass the time at camp creatively. Dorothy Yamashita still has several small, bird-shaped wooden pins her father-in-law carved by hand. And Tracey Tsugawa’s family treasures four pieces of sculptural wood fashioned by her grandfather.

But, these testaments to the resilience of the human spirit aside, the fact remains that for various reasons during World War II the United States maintained an extensive domestic system of involuntary incarceration. It’s hard reality to accept and one Tsugawa thinks we are still inclined to avoid, even in the language we use to describe it.

(Tsugawa) "The euphemisms that are used, I think really try to downplay the reality of what actually happened. The use of the words internment, relocation, evacuation, when what actually was happening is that people were, they were incarcerated. These were concentration camps in the United States. They were not death camps like what we saw in Nazi Germany or in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, but nonetheless these were concentration camps, and if you look at the photos you can see, you know, it was a pretty desolate existence."

(Wertlieb) The desolation itself is almost one of the characters in When the Emperor Was Divine. Author Julie Otsuka reads an excerpt.

(Wertlieb) The desolation itself is almost one of the characters in When the Emperor Was Divine. Author Julie Otsuka reads an excerpt.

(Otsuka) "IT WAS NOT LIKE any desert he had read about in books. There were no palm trees here, no oases, no caravans of camels slowly winding across the dunes. There was only the wind and the dust, and the hot burning sand. In the afternoon the heat rose up from the ground in waves; the air above the barracks shimmered. It was ninety-five degrees out. One hundred. One hundred and ten.

Old men sat outside on the long narrow benches, not talking, whittling away at pieces of wood as they waited for the hours to pass. The boy played marbles on the laundry room floor. He roamed through the barracks with the other boys in his block, playing cops and robbers and war. Kill the Nazis! Kill the Japs! On days when it was too hot to go out he sat in his room with a wet towel over his head and leafed through the pages of old Life magazines.

His sister lay on her cot for hours, staring, transfixed, at white majorette boots and men in their bathrobes in the Sears, Roebuck catalog. She wrote letters to her friends on the other side of the fence, telling them all she was having a good time. Wish you were here. Hope to hear from you soon. Their mother darned socks by the window. She read. She made them paper kites with tails woven out of potato sack strings. She took a flower-arranging class. She learned to crochet – "It’s something to do"- and for one week there were doilies under everything.

Mostly, though, they waited. For the mail. For the news. For the bells. For breakfast and lunch and dinner. For one day to be over and the next day to begin."

(Wertlieb) Author Julie Otsuka, reading from her book, When the Emperor Was Divine, the story of a family caught up in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Tomorrow we’ll conclude our series with reflections on the consequences of looking like the enemy in a time of war. You can find more about this series and the Vermont Reads project, and offer your own thoughts on our website, VPR.net.

For VPR News, I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

Explore the entire series: