(Wertlieb) As America went to war, thousands at home headed for a worrisome future in the custody of the U.S. government. And that’s where we pick up our series, Vermont Reads.

Good morning. I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the military to declare certain areas of the United States off limits to people with "Foreign Enemy Ancestry." That included Germans and Italians, but by far the most people affected were ethnic Japanese – 120,000 were sent into internment camps for the duration of the war.

Julie Otsuka traces this period in American history in "When the Emperor Was Divine," a fictional account of one Japanese American family’s war-time internment. And it’s our focus this week as part of Vermont Reads, the statewide reading program sponsored by the Vermont Humanities Council.

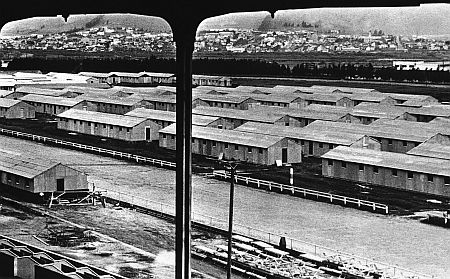

The U.S. Army was ill prepared to provide transport, food and shelter to 120,000 men, women and children.

This government film from that era recounts those efforts …

(newsreel)

(Wertlieb) The family of Dorothy Whitney Yamashita’s husband, Stan, was evacuated from the California fishing village of Terminal Island. But she says nothing was ready for them.

(Yamashita) "There was no provision made for them at all. No assembly centers had been established. No relocation centers had been built. Thanks to church people in downtown Los Angeles, they converted fellowship halls into, like a youth hostel, and my husband’s family lived there for three months."

(Wertlieb) Thousands of families experienced similar events. Tracey Tsugawa is a member of the Vermont Human Rights Commission and has studied this era extensively because of her own family’s internment. She agrees that facilities were non-existent at worst, and primitive at best.

(Tsugawa) "They didn’t have these buildings built, and in fact, the assembly centers were often at race tracks and fairgrounds. So the descriptions of those settings were pretty harsh in the sense that there is absolutely no privacy in the living quarters, in the bathroom areas, and everything, and the smell from the cows and the horses ‘cause they were literally being housed in horse stalls."

(Newsreel)

(Wertlieb) Lafayette Noda of Meriden, New Hampshire, remembers the conditions well. Now 93, he was born in 1916. His Japanese immigrant parents farmed in southern California. He was a graduate student when war was declared and he too was ordered to leave.

(Noda) "In our case in the Los Angeles area, many were removed to the race track, Santa Anita Race Track. I was part of a group of men put in a horse stall as a group, and provided straw to serve as bedding."

(Wertlieb) From Santa Anita, Noda was taken to Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming by train. He remembers the trip as being tedious and slow.

(Noda) "It was a rather hard trip in the sense that we were restricted to our place in the train and they said no lights at night. It was considered war time and they didn’t want the train to be recognized as being transport."

(Wertlieb) As it turns out, this was just the beginning of a journey that would take Noda – as it did many internees – far beyond his immediate destination.

(Noda) "and then from Heart Mountain I asked to be transferred to join my family at Amache Colorado. And then from Colorado then I went to Philadelphia and had contact there through the Quakers and was able to be helped in getting jobs to support myself again."

(Wertlieb) Today Lafayette Noda is professor emeritus of biochemistry at Dartmouth Medical School, and he’s still active at the family Christmas tree and blueberry farm.

Ultimately, the relocation policies of World War II carried him all the way across the country to New England, where he long ago put down new roots.

Experiences like this are part of the inspiration behind Julie Otsuka’s story. The characters in "When the Emperor Was Divine" are also transported – both literally and figuratively – from familiar surroundings to the unknown and beyond.

Experiences like this are part of the inspiration behind Julie Otsuka’s story. The characters in "When the Emperor Was Divine" are also transported – both literally and figuratively – from familiar surroundings to the unknown and beyond.

(Otsuka) The train moved slowly inland. Somewhere along the western edge of upper Nevada it passed a lone white house with a lawn and two tall cottonwood trees with a hammock between them gently swaying in the breeze. A small dog lay sleeping on its side in the shade of the trees. A man in a straw hat was trimming hedges. The hedges were very round. They were perfect green spheres. Someone – maybe that same man or maybe that same man’s gardener – had planted flowers inside of a red wagon next to the mailbox. In front of a wooden picket fence was a victory garden and a hand-painted sign that said FOR SALE; Behind the house was the dry bed of a lake and beyond the lake there was nothing but the scorched white earth of the desert stretching all the way to the edge of the horizon. On the map the lake was called Intermittent. Intermittent Lake. Because sometimes it was there and sometimes it wasn’t. It all depended on the rain.

"I don’t see it," said the girl. It was September of 1942 and her face was pressed up against the dusty window of the train. She was eleven and her hair was black and straight and tied back in a ponytail with an old pink ribbon. Her dress was pale yellow with wide puffy sleeves and a hem that was beginning to unravel. Pinned to her collar was an identification number and around her throat she wore a faded silk scarf. Her shoes were Mary Janes. They had not been polished since the spring.

"See what?" asked her brother. He was eight years old and his number was the same as the girl’s.

The girl did not answer. The lake had been dry for two years but she did not know. She looked down again at the map to make sure the lake was really supposed to be there. It was.

The girl had always lived in California-first in Berkeley, in a white stucco house on a wide street not far from the sea, and then, for the last four and a half months, in the assembly center at the Tanforan racetrack south of San Francisco – but now she was going to Utah to live in the desert. Some of the passengers were sick from the uneven rocking of the cars and the crowded compartments smelled of vomit and sweat and, very faintly, of oranges. The soldiers had left a crate full of lemons and oranges on the floor of the car earlier that morning. The girl loved oranges – she had not eaten a fresh orange in months – but she could not think of eating one now. The train lurched forward and she leaned over and put her head between her knees.

"I think I’m going to throw up," she said.

Her mother gave her a brown paper bag and the girl opened it up and began to heave. Her brother reached into the pocket of his trousers and gave her a tissue. She crumpled it in her fist as her mother slowly rubbed her back. "Don’t touch me," said the girl. "I want to be sick by myself." "

"That s impossible," said her mother. She continued to rub her back and the girl did not push her away.

(Wertlieb) Author Julie Otsuka, reading from her book, When the Emperor Was Divine, the story of a family caught up in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Tomorrow we’ll consider the practice of wartime incarceration. You can find more about this series and the Vermont Reads project, and offer your own thoughts on our website, VPR-dot-net.

For VPR News, I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

Explore the entire series: