(HOST) According to writer and commentator Castle Freeman, a literary milestone is coming up this week, recalling one of the most original voices in American literature.

(HOST) According to writer and commentator Castle Freeman, a literary milestone is coming up this week, recalling one of the most original voices in American literature.

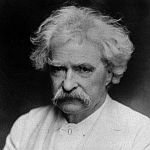

(FREEMAN) This coming Wednesday, we celebrate the centennial of the death of Mark Twain. The word "celebrate" is here used advisedly; Twain would have approved. He was, and is, America’s preeminent ironist, and in directing his unerring satire on the United States over half the 19th century, he became the country’s greatest literary performer.

Twain was born Samuel Clemens in 1835 in a Mississippi River town in Missouri to a family who had emigrated from Tennessee. He had grade schooling, worked as a printer and riverboatman, took up newspapering, and headed west, eventually becoming a roving reporter in the silver mining camps of Nevada. Later, in San Francisco, he began to find a wider audience for his stories and sketches. Soon Twain took to the podium, giving lectures and readings all over the US. He wound up an international figure, collecting an honorary degree from Oxford and embarking in 1894 on a much-publicized around-the-world lecture tour.

Twain is familiar to most readers today as the author of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, one of the two or three best known American novels. In a way, Huck’s monumental stature does Twain a disservice, for his vast body of writing contains several works of equal or greater merit, including Life on the Mississippi, Roughing It, The Innocents Abroad, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and scores of briefer efforts. These reveal a writer of inexhaustible invention, observation, artfulness, and wit. The multitude, vitality, and quality of Twain’s works are plainly the products of an authentic literary genius.

Twain is familiar to most readers today as the author of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, one of the two or three best known American novels. In a way, Huck’s monumental stature does Twain a disservice, for his vast body of writing contains several works of equal or greater merit, including Life on the Mississippi, Roughing It, The Innocents Abroad, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and scores of briefer efforts. These reveal a writer of inexhaustible invention, observation, artfulness, and wit. The multitude, vitality, and quality of Twain’s works are plainly the products of an authentic literary genius.

But a most unliterary literary genius he was, and a genius specifically in the American style, a style which Twain himself had no small hand in creating. In his writings and lectures, and in his conduct of his own celebrity, Twain showed the Americans what they were – or what they thought they were: a people practical, skeptical, energetic, a little crass, intelligent without being intellectual, and keenly alert to the fraudulent, which they detected on every hand.

Twain’s fame endures, but his achievement is undervalued. In part that is because he was a writer of sublime imperfection. His books are by no means exquisitely wrought. Huckleberry Finn properly ends 100 pages before its conclusion, because Twain, ignoring the sense of his own story, thought readers required a happy ending. And throughout his work Twain often padded outrageously – though it must be said that Twain’s padding is better than the essential matter of most writers, then and now.

In the end, Twain, like the fellow countrymen to whom he held up a mirror, was not a litterateur; he was in the game for cash and for fun, and he evidently enjoyed plenty of both. As for his reputation, Twain was sardonic about that, too. "Genius," he said, "elevates a man to ineffable spheres far above the vulgar world, and fills his soul with a regal contempt for the gross and sordid things of earth. It is probably on account of this that people who have genius do not pay their board, as a general thing."