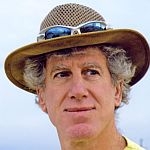

(HOST) Commentator Ted Levin has been watching bumblebees this summer, and studying bee behavior.

(HOST) Commentator Ted Levin has been watching bumblebees this summer, and studying bee behavior.

(LEVIN) Our bee balm is an explosion of magenta flowers – tubular and widely spaced – the floral equivalent of truncated fireworks. Bumblebees love it, of course. They’re drawn to the flowers from as far as a mile away. They sip nectar, flower after flower after flower, short, muscular tongues probing the depths of each bloom, bypassing the pollen-laden anthers. The harvesting of bee balm pollen appears to be left to tiny, solitary bees, whose tongues are too short to reach the nectaries.

When sated, the bumblebees fly over the lawn and the stonewall, and disappear into the gloom of the nearby pinewoods. They’re not east to follow, although ultra-marathoner and UVM professor emeritus Bernd Heinrich routinely used to track bumblebees to their subterranean homes; long distance running apparently having been a prerequisite for the writing of his classic book, Bumblebee Economics.

Bumblebees nest in abandoned rodent burrows. New queens, sole survivors from last year’s colony, awaken in late April, and fly low over the ground looking for suitable burrows, either in a meadow or a forest, depending upon the particular species; there are 267 species worldwide, mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, all in the genus Bombus.

Unlike a honeybee colony, a bumblebee colony dies with the frost, which is why bumblebees don’t stockpile winter stores of honey. There won’t be anyone around to eat it.

Queen bumblebees are big, slow, methodical fliers, which appear to defy the principles of aerodynamics. Around our home, they love red maple pollen and gather it in April to fed their first brood, which develops into sterile-female workers. Their job is to collect pollen and nectar, and tend the now hive-bound queen and all her subsequent broods until the colony collapses in the fall. Workers in most bumblebee colonies number no more than fifty, a rather small society as compared to that of a honeybee colony.

Because bumblebees store little honey they’re rarely the target of black bear and gray fox. They do, however, have a macabre enemy, a sort of fascist Bombus: a group of species, collectively called cuckoo bumblebees; all parasites.

Cuckoo bumblebees are homeless queens and drones (no workers). A cuckoo queen is a species-specific parasite. She finds an appropriate colony and then either kills or enslaves the host queen. Her extra hard abdomen protects her from defensive stings. Then, the cuckoo chemically alters the colony’s chain of command; workers ignore their own queen, her eggs and larva, and dutifully attend the needs of the cuckoo queen. It’s like a bumblebee version of Hitler’s march across Europe except it’s been happening every year since the Mesozoic.

I saw a cuckoo in the bee balm the other day. Because she doesn’t feed her own first brood, she had no need for a pollen basket on her hind legs. Instead, she drank nectar to fuel her search, a tough-hided, sting-proof bumblebee looking for a colony to plunder, a Bombus nightmare in yellow and black.