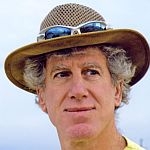

(HOST) Commentator Ted Levin has been thinking about an animal that can be a great help to farmers, but is only rarely seen in Vermont.

(HOST) Commentator Ted Levin has been thinking about an animal that can be a great help to farmers, but is only rarely seen in Vermont.

(LEVIN) What’s eight-feet long, as black as night, muscular, sinuous, legless, and when viewed in cross section, looks like a loaf of bread?

Give up? Well, it’s a black ratsnake. I’d accept the following pseudonyms however: eastern ratsnake, mountain black snake, chicken snake, or pilot black snake, a folklore-ish name implying that black ratsnakes guide timber rattlesnakes to remote wintering dens on the talus slopes of extreme west-central Vermont. Ratsnakes range from the edge of the Great Plains south and east from Minnesota and Texas along the Gulf Coast to Florida, north up the Atlantic seaboard into southern New England.

Several years ago, my son Jordan, and I found a black ratsnake looped under a blanket of oak leaves in Fair Haven. The snake exposed a few inches of dark skin to the spring sun, an reptilian solar collector. It remained motionless as we confirmed its identity. Finding a ratsnake in Vermont is a matter of knowing where to look, they’re rare and localized, and at the northeastern threshold of their range.

Elsewhere ratsnakes are so common you don’t have to look for them. They just appear . . . on the road, in the barn, the basement, the attic. A friend in South Florida, who lives on the apron of the Everglades once found a clutch of baby ratsnakes in his silverware drawer. In the Deep South they’re yellow like the yolk of an egg and long. One measured 101-inches, the longest official record for a native snake caught in the United States.

Recently, I was clearing limbs off a dirt road in Virginia, when I came across a five-foot female black ratsnake. In fact, the snaked look like a charred branch as she soaked up the morning sun. Ten minutes later, I caught a second snake in exactly the same place, an even larger male. This snake was on a mission, slowly gliding across the road, tongue flicking, reading the breeze.

I put both ratsnakes on the trunk of a black locust and they flowed up the tree like anti-gravity candle wax, black wavy lines, parallel and progressing, wedged in furrows of bark, upward beyond our view. Ratsnakes are quintessential arboreal predators. They feast on mammals and birds and bird eggs. To discourage nest-raiding ratsnakes, the red-cockaded woodpecker, a colonial-nester in southern pinewoods, nests only in living trees. The woodpecker drills a series of shallow holes below their nests; the skirt of sap that oozes from the holes stops the snakes.

Because a ratsnake may eat up to 200 rodents a year, farmers are not only willing to share their farm with them, they often release black ratsnakes in the barn, boasting of snakes six-feet long and twenty years old. As a hedge against mice and rats depredations, Long Wind Farm, in East Thetford, imported ratsnakes for their greenhouses. Whenever one escapes, it creates quit a fuss.

The Virginia ratsnakes eventually gathered themselves along a limb thirty-feet above our heads, braided together like an exquisite pigtail, tail tips flicking in rhythm, and consummated their rites of spring.