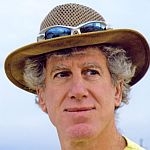

(Host) Naturalist and commentator Ted Levin says that this winter, one

(Host) Naturalist and commentator Ted Levin says that this winter, one

of our most iconic signs of spring has been with us all along.

(Levin)

During the summer of 2002, I planted several winterberry bushes on the

east side of the garden. Winterberry is a shrubby, deciduous holly that

belongs to the same genus – Ilex – as the better-known, thorny-leaved,

evergreen, American holly. As the name suggests, winterberry produces

fruit late in the year. Its bright red berries hug leafless branches

through much of the winter and when seen from a distance, give that part

of our yard a rosy blush. Winterberry look particularly dazzling

against a snowfall.

It’s often found in wetlands, along the edge

of ponds and lakes. The berries are neon bright in the winter gloom,

but winter birds eat them only when richer, fattier, more nutritious

berries have been harvested.

For ten years, my winterberry

bushes held their fruit right through the winter. But this year, they

were gone by mid-January – consumed by a small flock of equally colorful

robins.

Generally speaking, robins pass through Vermont in late

October and early November. Occasionally, we’ll see one in early

December, and once, many years ago, a small flock overwintered at a

dairy farm in Plainfield, New Hampshire, surviving on maggots mined from

the mountains of manure behind the barn.

This winter, a flock

of seven robins hung around our yard. During the warm weather of late

fall and early winter the robins ate earthworms in the garden; when the

weather turned cold, they ate the winterberries. And when the very last

berry was gone, the robins vanished.

There aren’t many birds as

utterly familiar as the robin. Their customary arrival in late February

is marked on calendars and broadcast in the media. They run

helter-skelter on lawns and nest on porches and in ornamental trees

around the yard, often at eye-level. At least in North America, robin’s

egg-blue is a universally known color.

Their spring and summer

activities are easy to predict, but where they make their winter home

depends on weather and food, and both are fickle commodities. One bitter

cold winter, more than twenty-five years ago, tens of millions of

robins descended on the Everglades. They were everywhere and hungry,

stripping berries from hammock bushes and chasing down little white

moths. They lined rain puddles like animated bathtub toys, a dozen or

more at puddle after puddle. But the very next winter the very same

region was nearly robinless.

Historically, the robin’s winter

range is in the Southeast, from lower New York to Georgia, though it’s

not uncommon for a few to stay here through the winter – in sheltered

spots where food is plentiful. But this year, flocks of robins have been

reported throughout our region, and that’s probably due to recent

climate patterns that have been anything but predictable.

Soon

after the robins departed, a red-bellied woodpecker appeared in the

yard, foraging in the crabapples. A bird that’s only recently extended

its range into Vermont – it’s another indicator of a warming world.