(HOST) All this week, as part of VPR’s special Champlain 400 programming, commentator Mike Martin has been looking at the New World through the "Eyes of

(HOST) All this week, as part of VPR’s special Champlain 400 programming, commentator Mike Martin has been looking at the New World through the "Eyes of

Champlain." Today, he offers a brief glimpse of the man himself.

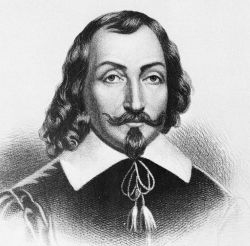

(MARTIN) You’ve probably seen the familiar portrait of Samuel de Champlain, the great French explorer and founder of New France. He has long dark hair resting on a broad white collar and a jaunty goatee with a pointy musketeer’s mustache. He has a high forehead, gently arched eyebrows, and just a touch of irony in his eyes.

The only problem is this man is not Samuel de Champlain.

In fact, no authentic portrait of Champlain exists, except for a drawing he made of himself in battle against the Mohawk – and his face isn’t visible. Most historians agree that the image of Champlain we’re accustomed to is actually the portrait of a shady French bureaucrat named Michel de Particelli. But even if we can’t picture his face, we can still get an idea of what kind of man Champlain was from his words and actions.

From his maps, drawings, and chronicles, we know that Champlain was an excellent observer. He was an accomplished cartographer who made beautiful, detailed maps showing French and indigenous settlements, as well as the local flora and fauna. And Champlain was a decent botanist and zoologist too; he catalogued scores of species with few errors – at a time when many still thought the Earth was the center of the universe. And while Champlain was no Michelangelo, he recorded powerful images from the New World. His drawings reflect a keen eye, a capable hand, and insatiable curiosity.

And we know that Champlain was brave. When he set out by canoe to fight the Mohawk in July 1609, he left most of his men behind, since, he explains, "ils saignerent du nez" or "their noses bled," meaning they lost their nerve. In battle again a year later, Champlain pulled an arrow out of his neck and kept on fighting. With help from his Native American friends, Champlain was only the second white man to run the dangerous La Chine Rapids in a canoe – even though he didn’t know how to swim. And Champlain wasn’t a whiner; about the only time he really complains is when he describes a "hellish" seventy-five mile retreat overland, when he was badly wounded and was carried in a basket on a Huron warrior’s back.

Champlain was also likeable. Henri IV received him often despite his low rank. Native American chiefs invited Champlain to stay with them – even to resolve their conflicts. The French soldiers and settlers looked to Champlain for leadership, even when he wasn’t the ranking member of the expedition. Isaac de Razilly refused to become Richelieu’s "Lieutenant for New France," insisting that Champlain was the better man. And Champlain was a "bon vivant" in the finest Québécois tradition; he founded the New World’s first dining (and hunting) club called L’ordre du bon temps, where the members enjoyed elaborate game dinners to help endure the long winter.

It’s sometimes said that great men can’t afford to be nice guys, but according to the historical record, the Father of New France was apparently both.