A group of Dartmouth students is spending the summer preparing balloons that could tell us more about the band of highly charged particles that surrounds the earth. Scientists want to know more about these so-called radiation belts that can make big trouble for spacecraft and satellites passing through them.

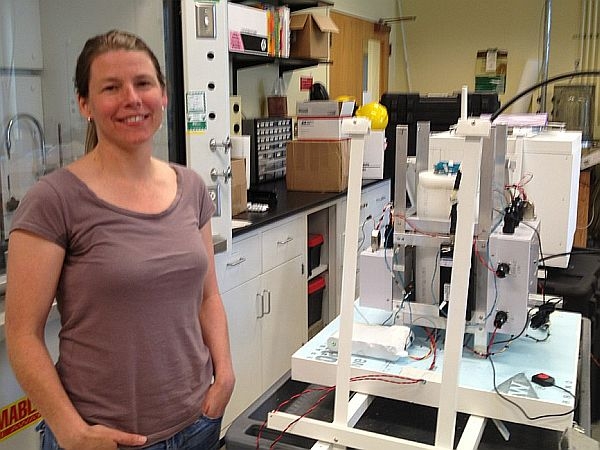

In a lab room chock full of metal and styrofoam, on a beautiful sunny day, a half dozen students are hard at work drilling holes. 10,000 of them. These metal frameworks will carry scientific instruments borne aloft by 25 fragile balloons next January, in Antarctica. The data will probe a big mystery about what scientists call the "radiation belt" around the earth.

"We have lots of space craft up there these days…defense satellites, weather satellites, your GPS satellites, all go through this region and so we’re trying to understand the region better, why the particles are trapped, and it’s a really variable region so we are trying to understand why the region varies so much," says Dartmouth Physics Professor Robyn Millan.

It varies, for example, in radioactivity. So passing through it at the wrong time, or in the wrong place, could harm spacecraft or anyone inside them. Millan says such damage has already been recorded, and now NASA will use these balloons to learn enough to prevent further harm. Equipped with GPS, they’ll send data to computers on earth. So a lot, literally, is riding on these balloons.

Bret Anderson is a team member who will help test the payloads."We attach the flight train and the parachute to the payload itself and then lift it off the ground and suspend it and make sure that the payload is level and then we weigh it to make sure we know how much weight we have on board," he explains.

In another lab next door, some of the finished frameworks are already sending test data to a laptop. Graduate student Leslie Woodjer says the data could make space travel better and safer for machines and humans, by providing them with better information about the earth’s radiation belts.

"I think we can effect something really big with this," Woodjer said. "I think it’s a great opportunity for science overall."

And for these young scientists

For more information, visit Dartmouth’s website here.